The corpus was created under TOME, a project financed by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (Sept 2023 - Aug 2025), with PI Petr Pavlas (Institute of Philosophy of the Czech Academy of Sciences). [https://tome.flu.cas.cz]

One of the objectives of the project was to assemble and analyse a digital corpus of early modern Latin printed books in the fields of alchemy and Paracelsianism.

The task of creating the corpus was assigned to the Digital-Philological group. Led by Georgiana Hedesan (Team Leader, TL), it comprised 3, then 4 PhD students (Research Collaborators, RC): Alexander Huber, Jana Kodetová, Ondrej Kříž and Jindra Kubíčková. For more information and background on the team, see here. [https://tome.flu.cas.cz/people/]

In addition, we received valuable support in deciphering and transcribing Greek text from Sean Coughlin, in data management from Vojtěch Kaše, and in data export from Jana Švadlenková.

1. Corpus Assembly

Early in the project, it was decided that the transcription process will be done by two means:

- Automatic transcription by Transkribus [https://www.transkribus.org/]

- Human editing by RC (first hand) and TL (second hand)

Transkribus is an AI-based tool that uses models to enhance the accuracy of transcription. The model we used during the first year was Noscemus GM6 [https://app.transkribus.org/models/text/noscemus-gm-6], created by Stefan Zathammer (Innsbruck) under the aegis of the NOSCEMUS project (Nova Scientia, PI Martin Korenjak, 2017-2023) [https://www.uibk.ac.at/projects/noscemus/]. The model was able to convert specific abbreviations into the long form (e.g. -que, -us, -tur, -um, …mm…, …nn…, -ae) and the long s (ſ) into normal s.

At the end of the first year, the TL created a new model using Noscemus as baseline. The model was trained to enhance detection of italics, capitals, as well as to convert certain abbreviations found in alchemical and medical texts. The model TOME 2.1 [https://app.transkribus.org/models/text/tome-21] will be released publicly at the end of the project.

A rigorous pipeline for transcription, annotation and metadata entry was established, as outlined below:

For more details on the transcription process, please refer to our publications on the topic.

2. Release

The corpus is available in its entirety in the Zenodo repository. Please click here [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14765293] for details and the latest release.

3. Corpus Selection

Several aspects were addressed in order to construct the EMLAP corpus. Although the comprehensiveness of the Latin alchemical printed corpus is desirable, it was not however possible to achieve this ideal within the TOME project. Consequently, a selection had to be made, and in doing so the following principles guided us:

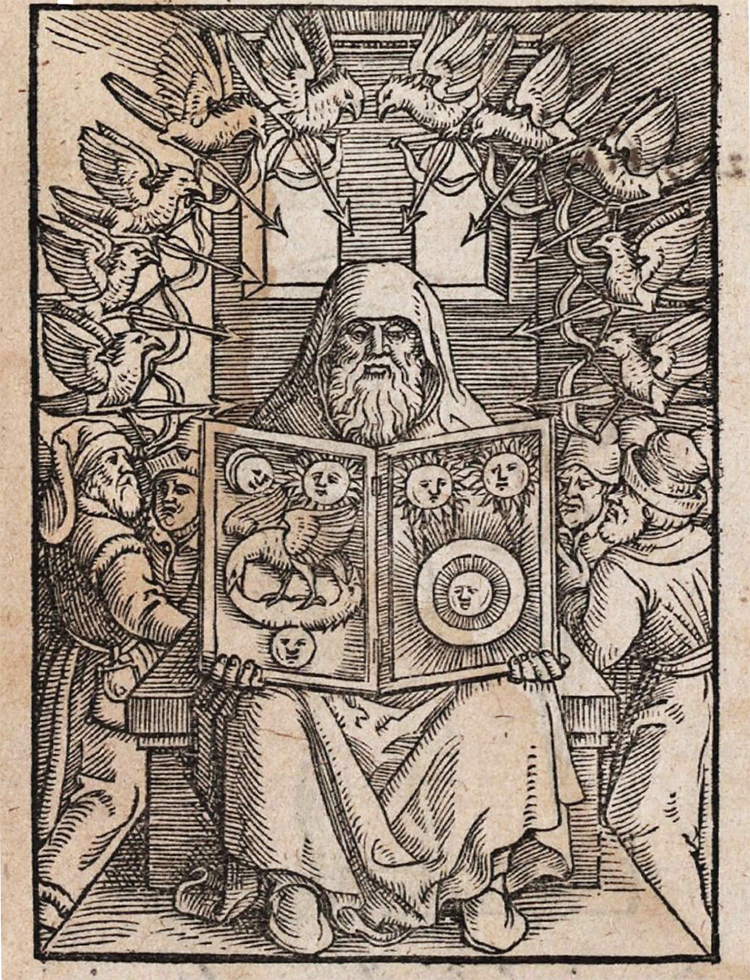

Importance: some publications were landmarks in the history of alchemy, such as Alchemia (1541), which included the first print of the Emerald Tablet in Latin, Petrus Bonus, Pretiosa margarita novella (1546), De alchemia opuscula I and II (Rosarium philosophorum) (1550), Leo Suavius / Jacques Gohory, Theophrasti Paracelsi Compendium (1568), Petrus Severinus, Idea medicinae philosophicae (1571), Artis auriferae (1572), Joseph Duchesne, Ad Iacobi Auberti (1575), Andreas Libavius, Alchemia (1597), Oswald Croll, Basilica chymica (1609), Musaeum Hermeticum (1625), J.B. Van Helmont, Ortus medicinae (1648).

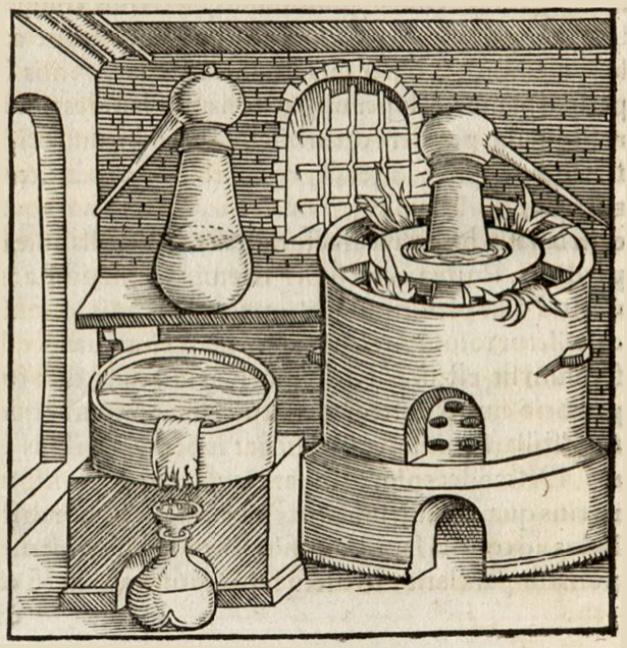

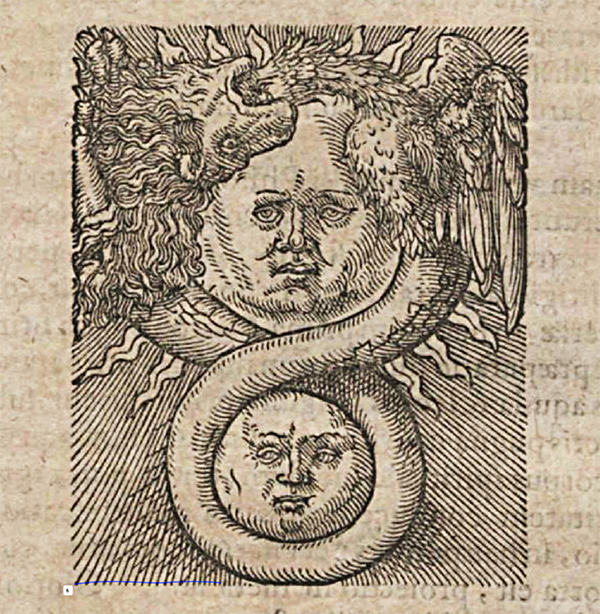

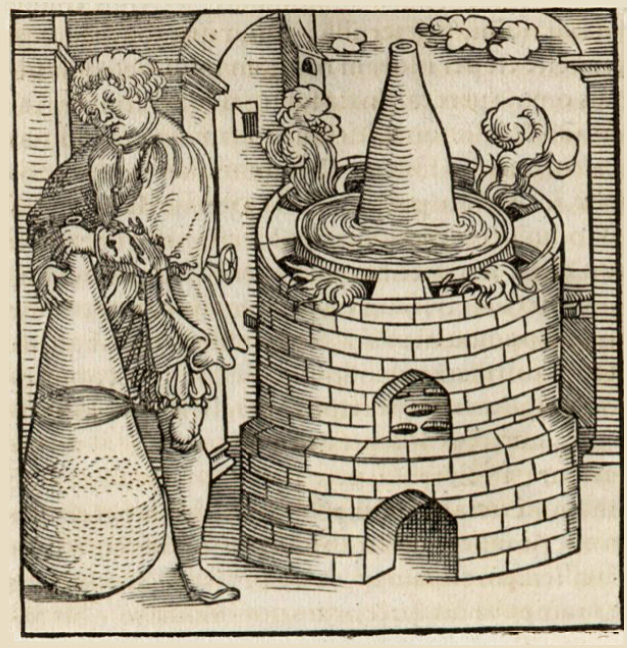

Variety: we took the view that alchemy was more than the transmutation of metals to gold (i.e. chrysopoeia). We provided a diverse collection that includes works related to distillation (e.g. Michele Savonarola, De arte conficiendi aquae vitae, 1532), so-called ‘books of secrets’ (e.g. Conrad Gessner, Thesaurus Euonymi Philiatri, 1552, Joachim Wecker, De secretis, 1582), texts attributed to Paracelsus (e.g. Labyrinthus medicorum errantium, 1553, Liber quatuor de vita longa, 1560), works related to alchemical / Paracelsian medicine (e.g. Petrus Severinus, Idea medicinae philosophicae, 1571, Joseph Duchesne, Ad veritatem Hermeticae medicinae, 1604), works connected with natural history as well as alchemy (e.g. Portaleone, De auro libri tres, 1584, Hagecius, De cerevisia, 1585), works related to spiritual or religious alchemy (e.g. Gerard Dorn, Lapis metaphysicus, 1570, De naturae luce metaphysicae, 1580). We also included some works that are not strictly alchemical but are relevant to the field, such as Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia (1533) and Paracelsus’ De natura rerum (1542).

High quality images: we aimed to provide a highly accurate transcription that can both be read by human readers and computers, and useful for various analyses. To be able to do this, we needed moderate to high resolution images. In some cases, unfortunately, we had to give up on some prints due to the low quality of the images.

Editio princeps: we generally tried to use the first editions of texts, with the exception of some cases where the first editions were not available digitally or were of poor quality.

The distribution of texts over 50-year time ranges is shown below:

4. Changes to Text

We have strived to reproduce the text as accurately as possible. However, to facilitate reading and analysis of the text, we had to operate certain changes that we are documenting below.

Abbreviations

Early modern Latin print exhibits a number of abbreviations that originate from manuscript shorthand. The Transkribus models we used (Noscemus GM6, then TOME 2.1) were able to automatically convert most of the regular abbreviations into long form.

Annotations

In the course of transcription, we decided that it is necessary to make annotations to reflect peculiarities in the text. These were deemed particularly useful to aid distant reading analyses. We first tagged marginalia in order to distinguish it from the body of the text. We also annotated foreign language inserted in the Latin text, alchemical / astrological symbols, weight symbols, superscripts, special characters or abbreviations (such as Rx for Recipe). See here for the detail on all the tags.

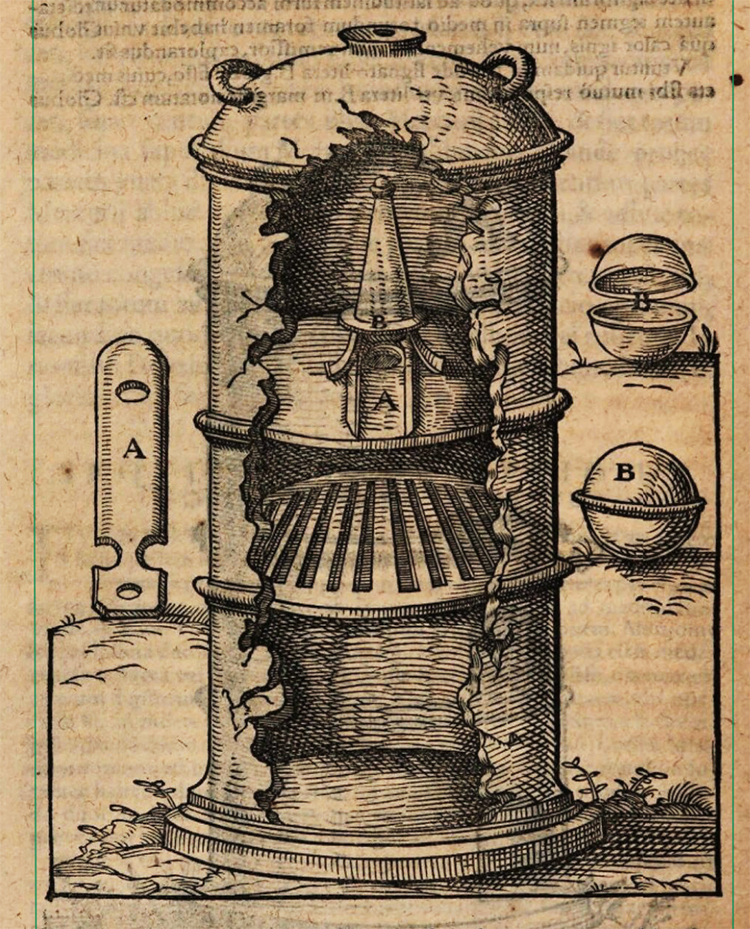

Images

Many alchemical texts, in particular, are illustrated. Where this was the case, we extracted the image and put instead a numbered marker: image 1, image 2 etc. We did not extract editor or printer devices or ornamental images.

Greek

In the case of larger Greek passages, we have applied the following conventions to ensure both fidelity to the original and readability:

- All original accent and breathing marks were retained; where the printed text placed them on the first vowel of a diphthong, we systematically moved them to the second vowel, in accordance with contemporary polyphonic practice.

- Punctuation and capitalization has been retained.

- We reproduced the accents as they appeared in the source, even where they departed from modern rules of accent placement.

- Where the original text omitted an accent or breathing mark and this created ambiguity with other words or inflected forms, we supplied the appropriate mark to aid clear reading.

- All Greek ligatures and shorthand forms have been expanded to their full spellings. Common examples include ligatures for καί, δὲ, and -οῦ.

‘Ramist’ Tables

Toward the late 16th century there was an increased amount of texts that featured what are usually called ‘Ramist’ tables, after the French logician Petrus Ramus who popularised their use. These were used to summarise knowledge in a visually sensible format via complex accolades; these tables are however difficult to reproduce in simple text. We have developed a standard that may be useful to use, with the caveat that occasionally authors use Ramist tables in an idiosyncratic or even abbreviated form.

More information on the text rendering of Ramist tables is given here.

Citations

Where citations were obvious from the text, such as in regards to biblical passages, we included that text between inverted commas “...”

Corrections

We have also decided that we will manually remedy printer errors when those are evident. These included:

- Where the printer did not include the hyphen (¬) for a word broken up at the end of a column;

- Obvious word errors, often in headers;

- Page numbering errors.

Where words and numbers were corrected we have put a [sic] at the end of the corrected word.

5. Publications

For more information and details on the transcription and the project, please refer to our publications list below: